Obituary

Donald J. “Old Warrior” Harris, beloved father, grandfather, great-grandfather, great-great-grandfather and wounded World War II veteran passed away peacefully while surrounded by generations of his family on March 8, 2023. He was 100 years old.

Born in Ontario, Oregon, on August 9th, 1922 to Roy and Fannie Mae Harris, Don was one of four children including older brother, Wayne, and younger sisters, Lois and Helen.

In the mid 1920’s, the Harris family purchased range land east of Malheur City where they built a ranch and bought several gold mining claims. Throughout the Great Depression era, Don, his brother, Wayne and his father mined gold by hand throughout the Dixie Creek basin in eastern Oregon. When not working on the ranch or mining sites, Don attended grade school in Brogan, Oregon from 1929 to 1935.

“I was about 10 when we started. Dad said he would keep the first 100 dollars each month from each claim and give the rest to us boys. That summer we pulled about 240 dollars from the first site. Dad said, ‘Wait a minute. You boys are richer than me! We need to renegotiate our agreement.’ Of course, Wayne and I conceded when dad joked about charging us rent. We did okay during the Depression.”

With the proceeds from their gold claims, Don’s father purchased a lumber mill where he made railroad ties for the Union Pacific Railroad. He also converted a flatbed truck into a school bus which he used to transport local children, including his own, to school in Brogan throughout the 1930s.

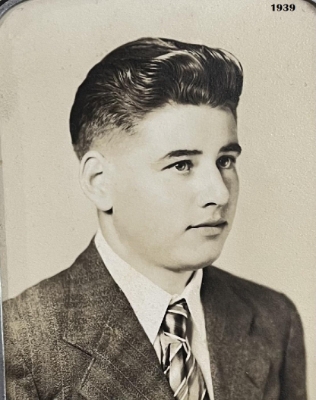

In the late 1930’s Don left home and moved to Vale, Oregon where he attended high school and met his future wife, Clara Musgrove. Don played football for the Vale Vikings, lettering in 1938 and 1939.

Following graduation in 1940, Don moved to Pendleton to work on his uncle’s ranch. For almost three years, as World War II progressed, he tended sheep on the rolling hillsides near the airbase that would eventually become today’s Pendleton Airport.

In the summer of 1942, as war raged so far away from those fields of peaceful, swaying amber, he would lie at night near the end of the air strip and watch the mighty bombers thunder overhead as they practiced touch-and-goes. It was under those brilliant starry skies, shepherding his uncle’s sheep, that he made the decision to join the military. Like his father (Roy) who had served in the U.S. Marine Corp during World War I, Don felt it was something he had a duty to do.

First, Don attempted and failed to become a pilot in the Army Air Corp in 1943. Don would say in later years that he believed some of his symptoms contributing to the failed physical exam could have been the result of a rattlesnake bite he suffered while stacking hay one summer as a teenager.

“I had the worst headache of my life for two weeks,” he said of the days following the snake bite, “I was so dizzy I could barely walk.”

Undeterred, in winter 1943, wanting to follow in his father’s footsteps, Don attempted to join the Marine Corp Officer training regiment, where he was disqualified by the results of an unexpected academic test.

“I didn’t know they were going to book test me,” he would say with a chuckle, “I couldn’t be a pilot because I got too dizzy, and who would have thought the Marines wanted a book worm. So, I figured I would try Ranger school.”

Don enlisted in the Army as part of the Expeditionary Force and completed basic training in the scorching heat of Camp Hawn, near Death Valley, California in Summer of 1943. In fall of 1943, he boarded a troop train bound for New York where he then embarked on a 3-week long, zig-zagging trip by passenger ship across the U-Boat-infested Atlantic ocean to England, along with 10,000 other U.S. soldiers. From September 1943 to late May 1944, Don’s unit secretly trained in England for what would become the greatest military invasion in human history.

D-Day, June 6, 1944

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, Don’s unit received orders to board a transport ship which would take them to a location off the shores of Normandy, France near what would become known to the world as “Utah Beach”, one of several locations along the northern coast of France where Allied Forces would invade Nazi occupied Europe. Once there, they would engage a critical mission to accompany Allied invasion forces on the beach head while protecting the movement of equipment, armament and personnel, and proceed inland, nearly 10 miles, to the French town of Saint-Mere-Eglise.

Unlike so many brave young men, Don survived the D-Day invasion. For nearly 4 weeks after, his unit pushed inland, fighting the Nazis and securing strategic geographic locations in northwest France. Don’s unit oversaw the establishment of several offensive fortifications where U.S. troops would install the most effective Anti-Aircraft Artillery positions of the war, protecting France from Nazi aerial attack.

General Patton

Later, in early July 1944, having secured the region around Saint-Mere-Eglise, Don and his fellow troops were ordered to be present at a large gathering to be attended by General George Patton. During the event, despite orders to stand at attention and salute, a handful of soldiers, including Don, refused to salute the General as he passed by with his aides. As Don’s commanding officer was preparing formal disciplinary charges, the General’s aide informed him that Don and his fellow soldiers were “correct in their decision to not salute General Patton, a high-ranking commander, under battle conditions, since it is detrimental to the security of the commander to identify them in sight of the enemy.”

Despite their exoneration by General Patton, the men were disciplined by being ordered to dig a latrine, which they did with laughter and enthusiasm. During their labor, several soldiers would stop and sarcastically salute Don and the working men as they passed by, some teasing them about using the latrine while they were digging it.

Sometime after the incident, Don and the other men came upon a trailer tank meant for storing drinking water. This one just happened to be filled with beer. Don would later tell the story:

“I can’t say for sure where it (the beer) came from. We were just told to go get the trailer. But I like to think I have a good idea who was responsible. But, I can’t say for sure.”

The fact that General Patton brewed his own beer during Prohibition only fueled Don’s suspicions.

Hedgerow

One morning in mid-July 1944, just before sunrise, Don woke to the sound of distant gun shots. He scrambled to his feet and, following his training, began moving toward the intermittent crack of rifle fire. He took cover along a hedgerow as he flanked toward the location where he believed the shots were coming from.

After several minutes of silence, however, Don presumed the incident was over. He moved through the hedgerow, rustling the foliage, and began walking back to camp. He had only taken two steps from the hedgerow when he heard the crack of a passing bullet, which narrowly missed his head.

Turning and raising his rifle, about 100 feet away in the early morning light, Don saw a dimly lit silhouette of a German soldier standing with his rifle aimed at him. As Don crouched and focused his sights on the middle of the dark figure, the German soldier immediately threw down his rifle and began raising his hands. But, before Don understood what was happening, there in the dark shadows of the hedgerow, he fired one shot, striking the German soldier in the chest, killing him instantly.

“It happened fast,” Don would say, “I had no way of knowing his intentions. He nearly killed me, and there was no way I was going to give him another shot.”

Despite mass surrender by German soldiers, Don’s commander listed the incident in the field report as a justifiable engagement. Had the German soldier tried to surrender without shooting, it might have been different. But the fact that he shot at Don first, then tried to surrender was, as Don would say…”a bad decision by him.”

Wounded in Action

On July 30, 1944, Don and his unit were ordered to accompany a movement of armament, equipment and infantry south toward La Mans, France. On August 1st, as they moved through the town on a stretch of roadway south of La Mans, which would later become a part of the original La Mans raceway, the U.S. convoy was attacked by German Luftwaffe planes.

During the attack, Don jumped into a nearby anti-aircraft gun turret and began firing back at the German planes. As he fired at a plane flying parallel to the convoy, Don felt what he believed was an ammunition box hitting him in the hip.

“I thought one of my guys had thrown ammo in the turret and hit me in the leg…”

As the plane flew overhead, Don, unable to look down, began to realize he was having difficulty standing. Still focused on the plane above as it turned back toward him, he began firing again. This time, as the plane flew over, Don watched several tracer rounds from his gun strike the underside of the plane. At that moment, he heard a loud voice.

“Hey, you’re shot!”

Not fully comprehending, and undeterred from the fight, Don began to slip in his own blood. Falling, unable to rise to his feet, Don heard the voice again, “I need to get you out of here!”

Don looked to one side to see the concerned face of an Army medic reaching for him and pulling him from the turret. As the two men fell to the ground, the medic was already working on Don’s wound, blood spurting in all directions. Realizing the bullet had clipped Don’s femoral artery, the medic immediately stuck his finger deep into the hole in Don’s hip, attempting to stop the bleeding. For more than 30 minutes, the medic remained by Don’s side, finger inserted, as they transported him back to the field hospital.

Along the route, the German planes circled again and fired on their truck. Don recalls several 20 mm rounds narrowly missing him as he lay on a stretcher with the medic close by.

“One round passed under me into the bed of the truck, another passed over my belly. It was very close.”

Finally arriving at the field hospital, the medical team was able to stop the bleeding and save Don’s life.

“It was hard for me to watch the doctors in that courtyard. I was never afraid for my own life, but I had to watch them walk down the line of dozens of wounded and seemingly casually pick the one’s they could save while skipping over the one’s they knew they couldn’t…even though they were still alive at that time. The doc pointed to me, ‘Take him’, and skipped over the next guy and I yelled, ‘What about him?’ The doctor looked at me and just shook his head without saying a word and kept on going down the line.”

During surgery, doctors determined the bullet had not only damaged Don’s femoral artery, but also perforated his stomach, punctured several inches of intestinal tract, and impacted one side of his scrotum. They also found several pieces of uniform and turret metal embedded in his pelvis and upper thigh. The surgeons operated for two hours, stitching vessels, closing wounds, and removing debris.

A Long Recovery

Don was transported back to England where he recovered in a hospital bed for 10 months. During his recovery, doctors anesthetized Don’s spinal cord to immobilize his lower body and control pain. The block completely numbed his body from the waist down.

Unfortunately, during the English winter of 1945, nurses inadvertently moved Don too close a wall heater which blistered the bottom of his feet.

“The nurses felt so bad. One of them came three times a day to wrap my feet and rub salve on them,” Don recounted with a smile, “I didn’t feel a thing. But I didn’t tell her. She was pretty, and I liked the attention.”

Don was awarded the Purple Heart and received a field promotion to the rank of Corporal. As several of his fellow furloughed soldiers came to congratulate him, they informed Don that the medic who saved him had returned to the battlefield that day and, along with other medics, had rescued the pilot of the plane Don had shot down.

And, that the German pilot was in the bed next to his.

Over the next several days, Don was able to talk with the German pilot. Ironically, the pilot was a German-American who had been living in Chicago when the war began. Answering the call to duty to defend the “fatherland”, he had returned to Germany and became a pilot for the Luftwaffe.

“We were just doing our jobs. Following orders,” Don would say, “He was actually a nice guy. He and I had no animosity whatsoever. He shot me, and I shot him. Then it was over, and we both got to go home.”

Going Home

Don returned to the United States in Summer of 1945 where he remained in a hospital in San Diego receiving physical therapy for three months. Once he began to walk again, he returned home to Oregon where he proposed to Clara. The two were married in December, 1945.

The couple moved to Nevada and soon had their first child, Evelyn, in 1947. Struggling to find work, Don and family returned to Vale where their second child, Albert, was born in 1949. After the birth of their youngest child, Donna, in 1950, they moved to Corvallis where Don attended Oregon State University, studying Engineering. Prior to graduating, however, the family moved again to Klamath Falls where Don completed his bachelor’s degree at Oregon Institute of Technology in 1953.

In 1953, the family moved to Long Beach, California. Don worked for Boeing and, later, with Douglas Aircraft as an Engineer. He then accepted a position with the State of California, Highway Engineering Division, moving the family to Marysville, Ca. in 1956, where he served as a regional supervisor until 1972. Given credit for his military service and wounds received in action, he retired in 1972, at age 50, with full pension and VA benefits, moving the family to their final home in Oregon.

An Epic Life Lived

In 1980, Don tragically lost his left eye in a mowing accident. However, as was the case throughout his life, he accepted the incident in stride and continued to live as he wanted, disregarding limitations. He remained physically active until his death and credited his longevity to his “exercises” and working outside. Despite the wounds he received living this life, Don continued to work in agriculture, operating farm equipment, cutting firewood, construction work and duties around the family’s homestead. In 1985-86, he helped engineer and build a roof over the football field grandstands at Crow High School, where his grandsons attended.

In 1993, Don accompanied his grandson, Patrick, on a month-long trip across the U.S. The two stayed for several weeks in Branson, Missouri, seeing many Country music shows and visited attractions along the way, including the Grand Canyon, Las Vegas and the Rocky Mountains. On the way home, the two narrowly escaped a tornado in Kansas and were nearly struck by lighting outside of Kansas City.

In 2002, Don was driving to a hardware store when he was stopped and cited by a police officer for speeding. At his court hearing, Don told the judge that this was the first ticket he had ever received in his life. The judge laughed and playfully said, “I don’t believe you.”

The judge ordered a review of his driving record and discovered Don was telling the truth. The judge apologized to Don and dismissed the case. Don continued to drive his own car into his early 90s until finally, voluntarily surrendering his license in 2014.

“What do I need to drive for? I have plenty of kids and grandkids to haul me around if I need it,” he would say.

Don spent his remaining years at his country home in Crow, Oregon, raising Christmas trees, gardening, growing flowers, working for the local school district, and supporting his grandchildren throughout their school and sports participation. He enjoyed telling stories about his life, visiting with friends, watching Oregon Ducks and 49er football, and reading Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour novels, which he did for 40 years.

Don turned 100 years old in August 2022. He lived during the terms of 17 U.S. Presidents and passed away as one of the last remaining members of America’s “Greatest Generation” who have lived through some of the most significant events of human history, including the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, Prohibition, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Fall of the Berlin Wall, 9/11 and wars in the Middle East. He was preceded in death by his wife, Clara (March 8, 2008, the same day of his passing, 15 years earlier), his father (1972), his mother (1997), his sister Lois (2009) and sister Helen (2011) and his brother Wayne (2018).

Don is survived by his children, Evelyn, Albert and Donna (husband Danny); six grandchildren, James (wife Hillary), Patrick (wife Terri), Jason (wife Aimee), Elizabeth (husband Scott), Danny Jr. (wife Erin) and Lydia; seven great-grandchildren and four great-great grandchildren.

Services arrangements through Musgrove Funeral Services. Contributions can be made to the Silver Star Families of America Foundation.

Events

There are no events scheduled. You can still show your support by planting a tree in memory of Donald Jay Harris.

Plant a tree